Taste is one of the few things where the body reveals its opinions before the mind has time to. A good Banganapalle mango, a perfectly seasoned dip, an Oishii pack of strawberries: these things simply happen to you. So it's strange when a taste moves in the opposite direction, from pleasure to disgust, and stays there long enough to feel like a permanent part of who you are.

Chocolate did that to me. Or I did it to chocolate. It's hard to say which.

I used to like chocolate and suddenly when I was seven, I didn't anymore. This response has stayed true across brands, contexts, and types of chocolate, including ones where cocoa is only a minor component.

Now this would be unremarkable if chocolate was just another food. But chocolate is a globally engineered pleasure technology optimized for multisensory satisfaction (all buzzwords intended). Billions of dollars of industrial R&D exist to ensure chocolate tastes good. To dislike chocolate is to reject one of the most successful sensory inventions humans have ever produced.

Meme from reddit casually summarizes my life

An important thing about taste is that it pretends to be personal but much of it is outsourced to a bunch of other systems. Culture is one of them, chemistry is another, followed by biology, memory, industrial processing and geographical temperature variations. A lot of what we call taste is simply an amalgamation of these.

how much of taste is really shaped beyond individual preference?

The idea that eating is more than simply a way to sustain ourselves is not something we hear about every day, or even think about. But it's central to how we decide what's socially and culturally acceptable to eat, what we choose to eat, and why we eat certain things at all.

A crude example: imagine you've just eaten the most tender, well-cooked, great-tasting meat of your life. You ask the host what it was, and they say human. You would probably throw up on the spot or feel an intense gag reflex, entirely because of the idea of what that meat was. The host might even be lying. Maybe it was just well-cooked impossible meat. Without any way to confirm the truth, your disgust would still be visceral, and you probably wouldn't be able to eat meat normally for a while. Your perception of that tasting experience changes completely based on an idea given to you, even if it may not be true and you have no way to prove or disprove it immediately. So you really could say that we taste with our brains not just our mouth. And that it's an experience in a way socially constructed and not just independently tasted. Maybe I have a conceptual disgust unrelated to the sensory properties of chocolate because growing up my mom told me that chocolates had 8 cockroach legs in them. This is statistically true, and accounted for in FDA regulations. But it doesn't explain physical disgust for over a decade.

Parallely, what if you were introduced to a food by being told that it was going to taste terrible. Extremely bitter. Horrid to consume, maybe even something that would make you vomit? Dr. Briggs from UNC's Anthropology Department, who specializes in food, conducted a case study in her class where she did exactly this. She would describe a drink as completely awful, very bitter, and likely to make students gag. Then she would invite the class to taste a brewed tea she made and ask how many wanted to try it. Only half the class would raise their hands; the other half refused. And despite having no real information about the tea, the likelihood that the students who tried it would experience the reaction she described was very high, simply because of the idea planted in their minds. So if your first experience with a food is framed as bitter or bad, how much does that influence your taste? And how much of what you end up perceiving is actually a reaction to the expectation rather than the food?

Another example is the placebo effect with wine: when the same wine is labeled differently. One as 'expensive' placebo, one as cheap. People will consistently report 'expensive' wine tastes better.

Language shapes taste too. The nose and the brain work together to interpret flavors but without language, can you interpret them in the same way? Tamil, for example, has karakarappu (கரகரப்பு, crispy with a sound), urundu (உருண்டு, round, dense chewiness), menmenappu (மென்மெனப்பு, cloudy delicate), ippu (இப்பு, mildly saline), and kasappu (கசப்பு, medicinal bitterness rather than regular bitterness). If language doesn't name a texture or taste in detail, do you perceive it less vividly?

global taste variance that followed the mass production of chocolate

Once upon a time, chocolate used to be known as a very, very different thing from what it is today. Throughout the Mayan and Aztec civilizations, cacao beans were used to brew a frothy, bitter beverage sometimes with spices like chili and maize rather than the sweet, sugary bars that we know today. Chocolate houses started in London around the 1650s functioning as early third spaces very similar to cafés as we have today, but never took off since they were more of a prestige signal than an enjoyable drink.

If you directly tasted a cacao bean from the pod, it would taste extremely bitter and absolutely nothing like chocolate that we know today. Chocolate doesn't taste like chocolate until you force chemistry, physics, microbes, and heat to cooperate. The flavor is engineered through a flow of reactions that turn bitterness, acidity, and plant tissue into something people actually want to eat.

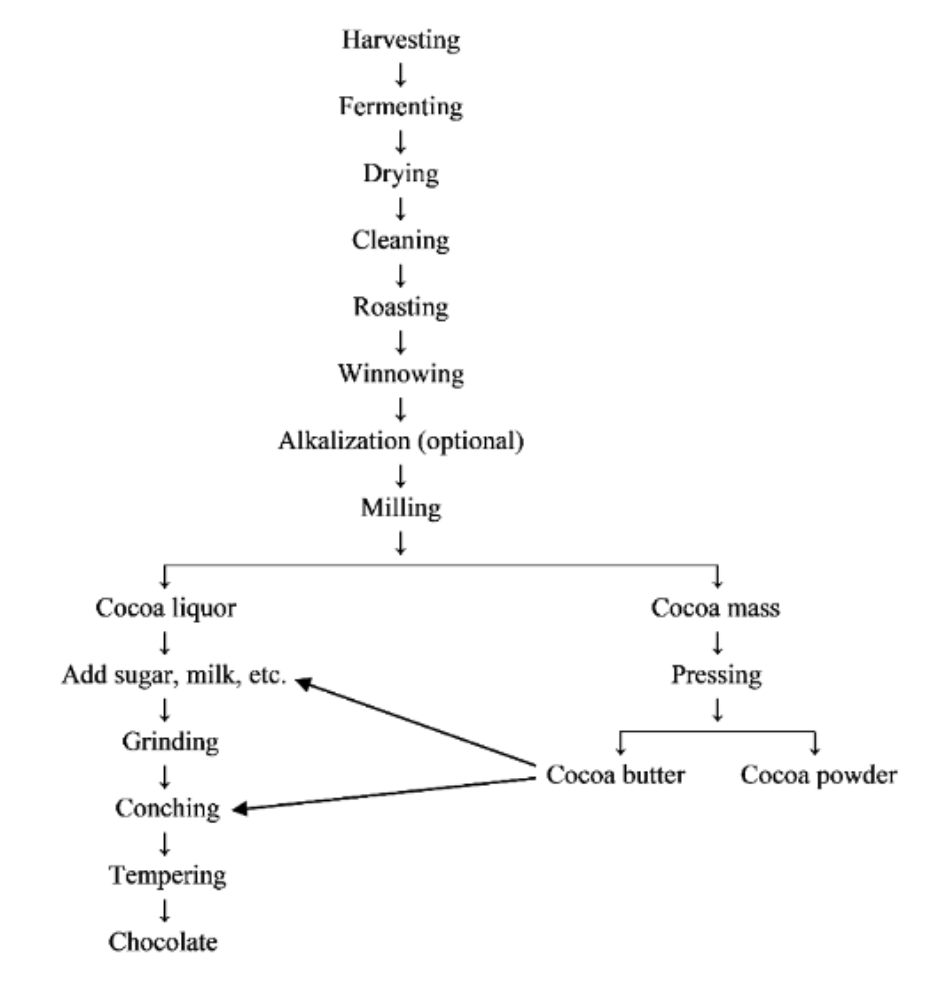

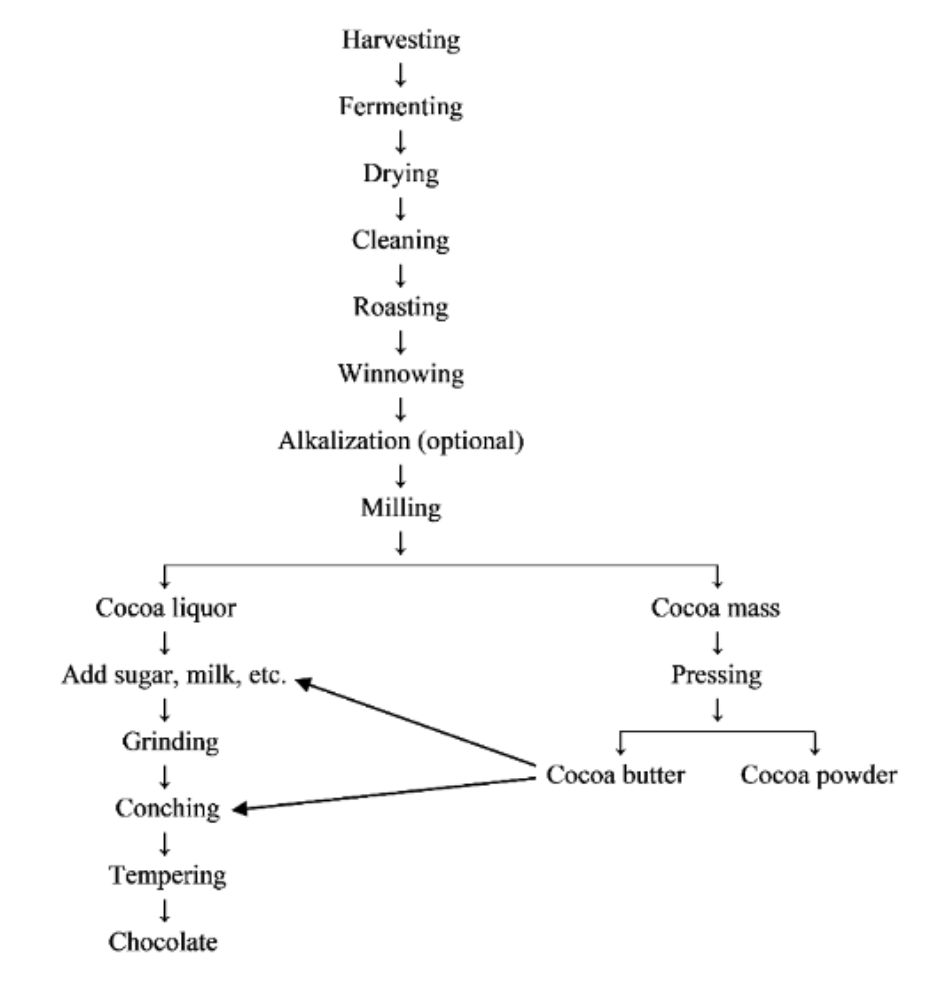

To understand the history of chocolate, we need to understand how it is created from a cacao pod.

Heaps and heaps of cacao are collected and fermented in a very specific way. Fermentation destabilizes the bean. Cell walls and vacuoles are broken down, which activates endogenous enzymes (like polyphenol oxidase) and generates esters such as ethyl acetate and isoamyl acetate that contribute fruity notes. Through this controlled microbial heap, chocolate gets broken down from complex molecules into simpler ones that can bind with other chemicals and eventually form the flavor compounds.

Flow chart of chocolate manufacture

After the raw cacao beans are fermented, they are roasted, activating the Maillard reaction, where reducing sugars react with amino acids at high heat at ~120-150°C. This is the same chemistry that makes bread crust taste like bread crust, and coffee taste like coffee. Roasting is where chocolate actually appears.

Essentially chocolate was pretty disgusting for our modern taste buds for most of its history. It was only in the 1800s that it became closer to what we know today.

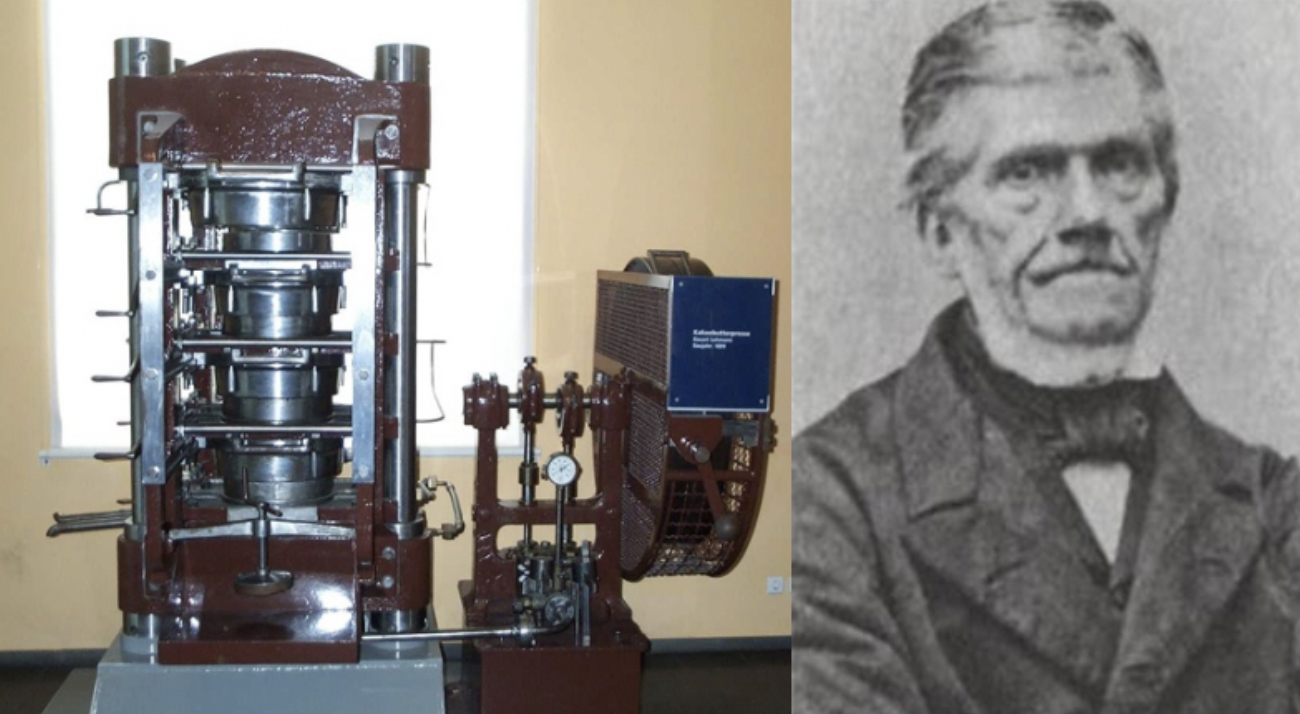

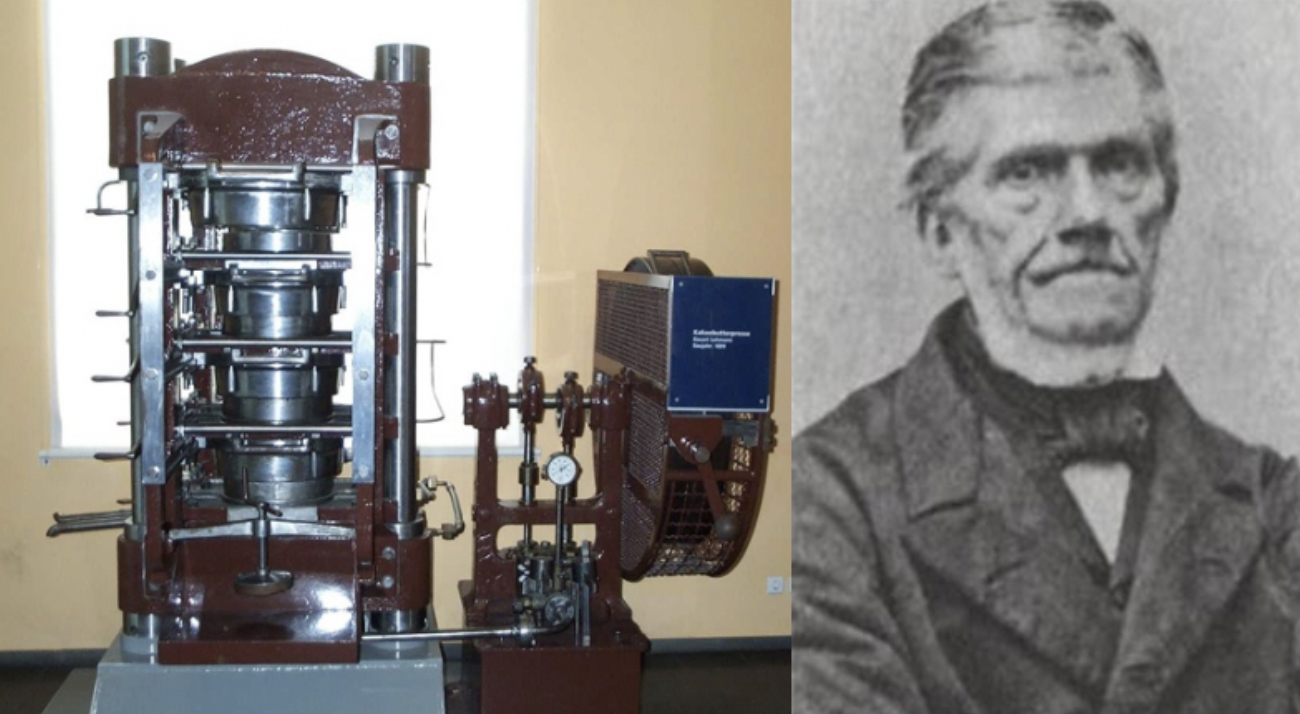

Big man CJH and the Chocolatinator 3000 ultra pro+ (named by me)

In 1828, a Dutch chemist named Coenraad Johannes van Houten invented the hydraulic screw press. This device separated cocoa butter from cocoa solids and marked the rebirth of chocolate. It's nicely written about here if you're interested in reading more. By pressing roasted cacao mass at high pressure (typically 400-500 bar), he could remove most of the fat content:

Roasted cacao mass (solid/liquid mixture) → cocoa butter (l) + defatted cocoa cake (s)

By defatting the cocoa powder it became easier to dissolve in water or milk. In other words without this Dutch machine chocolate would've stayed a bitter frothy drink forevaa.

Then the cocoa butter removed in this process was later recombined with sugar and cocoa solids (and eventually milk, after Daniel Peter and Henri Nestle added condensed milk in 1875-1879) to create modern milk chocolate.

And the fun only now begins.

With this newfound machine chocolate became more of a global wonder instead of a localized one. It meant that different countries could use cacao powder since the powder itself could be exported cheaper than exporting cacao pods in specific conditions and post-processing them. Different countries started formulating their own chocolates in different ways.

In America, butyric acid created from fermented milk is used in chocolate and it gets a rangy flavor profile. Butyric acid is also a compound found in vomit, which earned Hershey's chocolate the nickname of vomit chocolate.

In Europe, chocolate has a lot more cocoa-content regulations for chocolate to legally be called…well, chocolate. Their way of processing milk is very cream- and dairy-heavy, and that gives a darker flavor profile and lower acidity. In the UK, the milk is generally powdered, which gives a higher caramelized, sweet dairy flavor.

In equatorial countries, because of the higher temperature, cocoa butter is replaced with vegetable fats to create heat-stable formulations. And because chocolate is heated, refrigerated, and melted so often, there is a loss of volatiles and aromatic compounds, which mutes or tends to mute the flavor in more temperate conditions.

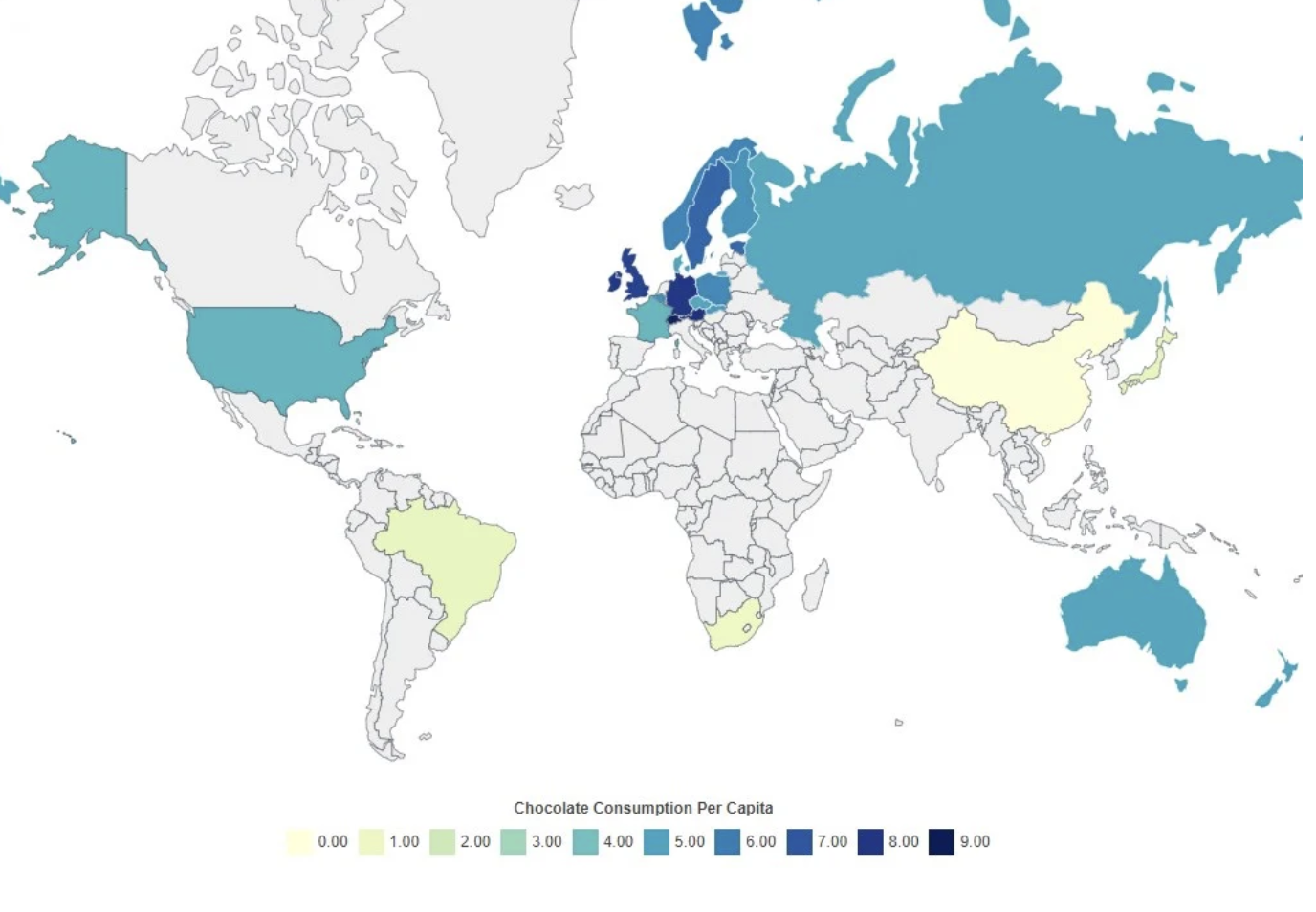

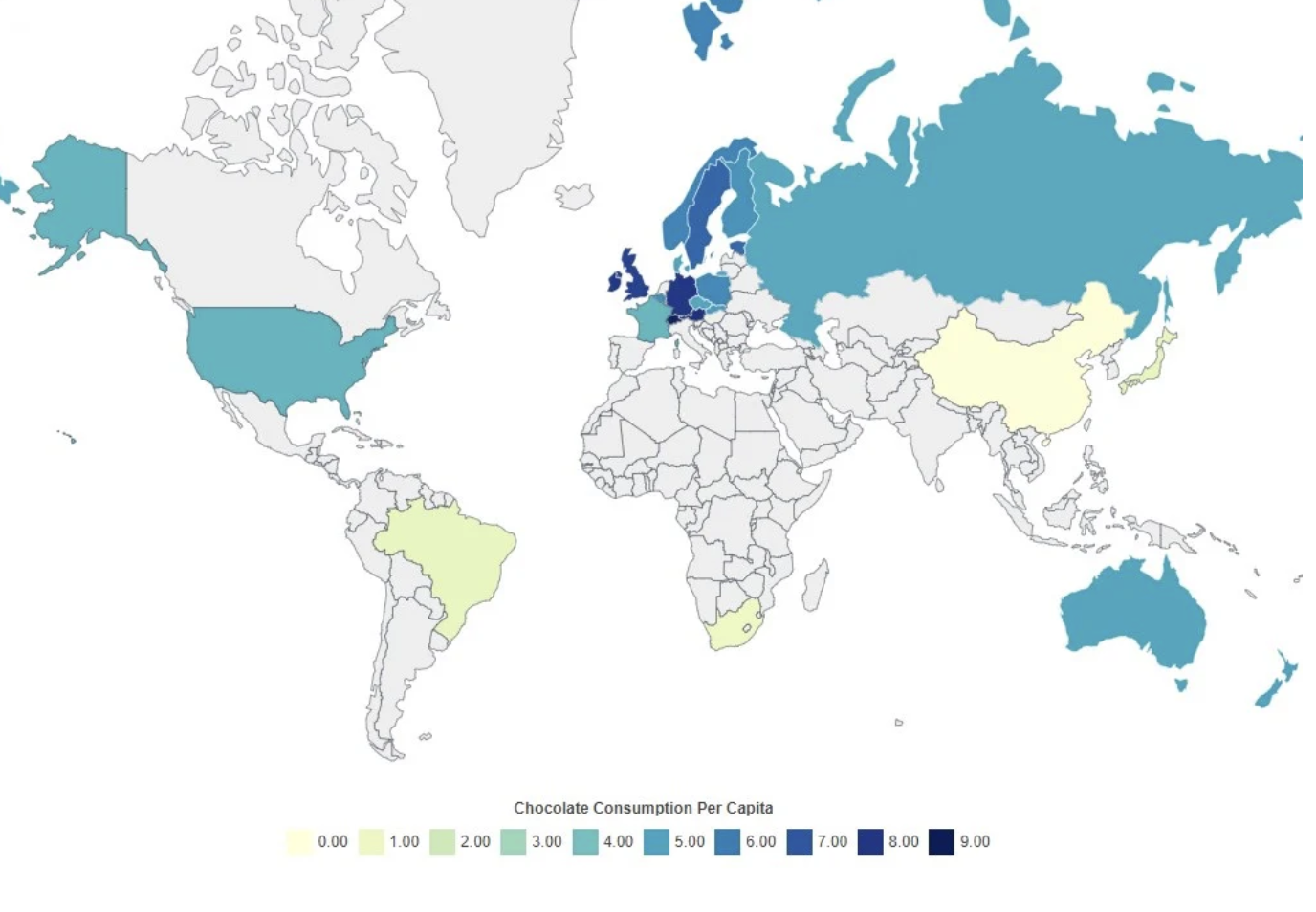

Chocolate consumption per capita

And an interesting fact is that Europeans consume more chocolate than Americans. America is not even in the top 16 of the 20 countries that consume chocolate, because Americans prefer chocolate-flavored things rather than chocolate itself. And in colder European climates, chocolate stores and tastes better, reinforcing its role as a staple.

∴ Chocolate isn't the same everywhere, so there's no such thing as chocolate independent of the region, its legal definitions, climate, and dairy technology.

my personal perception of taste - an investigation

case introduction

The earliest memory I have of eating chocolate was when I was three: eating them in strollers, falling prey to the grocery store child-sized checkout shelves, and absolutely loving halloween. My next memory of chocolate was when I was five and only Ferrero Rochers and ₹10 Dairy Milks. I had also just moved back to India with my family at this point.

And then I was seven. I magically did not like chocolates anymore. Not the way I didn't like vegetables. But in a way that would induce an intense taste of disgust in my mouth.

I kept testing myself just to be sure. Each attempt ended the same: one nibble, a flinch, water, and the rest in the bin. Even now I can detect chocolate in the faintest hints in buttercream, milkshakes, foods that 'shouldn't' even taste like it. Somehow I always catch it.

An important question here is: was I biased? I don't think so. The reaction remains the same regardless of what it is that I'm eating, whether it's labeled or not, if it contains chocolate in any capacity whatsoever, regardless of what situation I'm in. I used to tolerate white chocolate a bit more, but still would never choose to eat it. I just don't like it. ( I test this in the conclusion ;)

If I have no memory of what caused such a drastic change, what happened between loving and hating it?

I've been told another story by my mom. I was four, it was Halloween and I got a huge haul of candies, maybe three or four hundred pieces. I proceeded to do the only normal thing possible a child destined for STEM might do: sort all the chocolates in neat piles by type and then ate them in batches of ~forty. I was almost three-fourths of the way in when I decided to give up and not eat the rest of the chocolate anymore. After some attempted intervention, my mom decided it was fine. I had milk teeth, and they'd fall out anyway, so what was the harm? (pro parent move right there).

Maybe multiply this 3x

Now, I don't remember this. So it brought up the question, is a memory of disgust stored in the brain even if we can't recall it consciously? How can your perception of a certain sense completely change even though you don't remember anything particular that led to that?

And if I could 'acquire' hate, does that mean I could acquire the taste back?

Relevant facts:

| Age range |

Location |

Chocolate status |

Proof via memory (mine or someone else's) |

| 1-3 |

India |

Unknown |

|

| 3-5 |

USA |

Normal liking of chocolate |

I ate chocolate normally. Was a willing follower of the grocery store checkout lane trap |

| ~4 |

USA, Halloween event |

(Alleged) overconsumption event |

Many hundreds of chocolates were eaten |

| 5-7 |

India |

Selective preference |

Narrowed chocolate choices to Ferrero Rocher, Cadbury Gems and ₹10 Dairy Milk bars |

| 7+ |

India |

Aversion mostly, still had oreos and white chocolate |

Rise to fame via philanthropy of chocolates |

| 9+ |

India |

Complete aversion |

Realisation that even white chocolate and oreos weren't cutting it for me anymore. |

| Sometime 5<x<10 |

India |

General dislike of bitter compounds |

Parallely noting that I didn't like coffee, caramel, jaggery alongside chocolate |

hypotheses

1. genetic

If chocolate is engineered to appeal to senses and they don't to mine, then my guess is that some part of the tasting chocolate pathway isn't working for me.

The roasted, nutty, cocoa-like notes we associate with chocolate come from pyrazines and other Maillard reaction volatiles. They're detected by olfactory receptors and humans have ~400 of them that are all highly variable (for reference dogs can have ~800-1000 OR genes which is why they can smell a lot better than us). If my OR's are more sensitive to these compounds, then they might register for me as chemically wrong. This explains my consistent dislike for browned, caramelized, roasted chemical pathways like coffee, caramel, jaggery, and most sweets on top of the general chocolate dislike.

Bitterness sensitivity adds another layer. Genes like TAS2R38 influence how strongly people detect bitter compounds like theobromine and caffeine that are in chocolate. And because taste is ultimately interpreted by the brain and not just the tongue, chocolate may be producing a pattern of sensory input that my brain interprets as aversive rather than enjoyable. Like most genes, you inherit one copy of this gene from each parent and they can be either low or high sensitivity. Let's assume: H = high-sensitivity allele; h = low-sensitivity allele

a. hh: Two low-sensitivity copies = meh

b. Hh: One high + one low = hmm, bitter

i. Mom: likely Hh

1. Doesn't like chocolate but not nearly as strongly as me, she'd still eat it if given. Loves coffee. Eats bitter gourd

ii. Dad: likely Hh

1. Doesn't like milk or white chocolate at all. Or coffee. But loves dark chocolate and bitter gourd.

c. HH: Two high-sensitivity copies = WHY IS THIS POISON

This theory also fits neatly into a Punnett Square:

|

Mom (Hh) |

| H |

h |

| Dad (Hh) |

H |

HH |

Hh |

| h |

Hh |

hh |

It's possible that these sensitivities didn't happen earlier because some genetic traits show delayed phenotype expression. Aka certain taste and smell sensitivities only become noticeable when certain receptors mature or there's been enough exposure. This could explain why the aversion emerged after seven even if the genes were present throughout.

2. geographic

Chocolate is technically closer to being a composite material rather than a snack with the amount of technicalities that go into engineering it. It only feels simple because the engineering to hit multiple sensory systems at the same time is perfect (texture, aroma, fat melt curve, sweetness) when it works. When it doesn't, you immediately notice: it blooms, it melts wrong, it tastes flat, it snaps instead of melts, or melts instead of snaps. Which means a technical break can easily make chocolate feel wrong

a. Cocoa butter is polymorphic and can solidify into six different crystal structures. Only Form V tastes 'right'. Tempering is the crystal engineering step of the chocolate making process that makes sure this lattice is correct. The snap you hear when chocolate breaks is a fracture in this crystal and is specifically engineered for. Legend says that the airpods case snap is inspired by this /s. When the butter melts due to non ambient temperature conditions during transportation, or even using a formulation not designed for that particular region, it recrystallizes into the wrong polymorph, it blooms. Physically this results in chalky surfaces and chemically makes chocolate taste more muted

source

b. Cocoa butter melts sharply at ~33°C, which is just below body temperature. Below this temp it's solid and stable, and it collapses when higher. Ie, it fails exactly when it hits your tongue releasing an array of complex flavor molecules. This is what breaks when the storage temperature changes. To account for this, formulations around the world have some differences, further changing its flavor profiles.

Although I think this hypothesis is very likely to have played a role in my dislike for chocolate there is too much variance to conclude anything with certainty

3. overload from halloween event

Conditioned Taste Aversion (CTA) is the term used for physically bad experiences affecting your perception of the flavor. Eg, you get food poisoning and don't like the food that led to it for a while. This is a way the brain tries to prevent you from consuming things that may be harmful to you. This can happen after a single exposure and last for a long time.

Con of this theory is that CTA is usually very specific and doesn't explain why I dislike many kinds of chocolates, not just the types I had that Halloween. For eg, I am very sure I didn't have Dairy Milks or white chocolate then.

case conclusion

Genetically I may just be wired with more sensitive olfactory and bitter receptors. Geographically the chocolates I grew up with may never have matched what my senses were built to enjoy. And the Halloween binge adds a textbook moment for conditioned taste aversion, even if I don't remember it now. So the simplest conclusion is that all three interacted.

so can I actually reacquire the taste

The miracle berry (Synsepalum dulcificum) temporarily converts sour to sweet by binding to the sweet taste receptor (T1R2/T1R3) and conditionally activates it under acidic conditions, rerouting sour inputs into perceived sweetness. There is no known compound that cleanly inverts bitterness in the same way. But inventing one would seem promising.

Another strategy: Bitter perception can be masked by sodium ions or other antagonists that interfere with TAS2R signaling. A more speculative approach would be a bitter-modifying molecule that blocks high-affinity TAS2R receptors, similar to miraculin but acting as an antagonist rather than a conditional agonist.

experimental results

Hypothesis tested in three different continents

Experimental log:

| Test continent |

Test location |

Notable conditions |

Brand |

Notes |

| Asia |

Chennai, India. 28°C |

Sodium suppression test. Some salt was licked before tasting the chocolate |

Munch - Nestle and Dairy Milk - Cadbury. Both have localized formulations |

Biggest surprise was that it actually did taste less bad when I tasted salt first!! I didn't particularly like it but I could certainly tolerate the flavor which is a massive leap in the past decade

Very promising for further mods that make chocolate go from neutral → nice, or bitter → better (blame Betty and her butter for this joke, iykyk ;) |

| - |

|

Yeah…went back to dislike for this one. |

| Europe |

Frankfurt, Germany. 6°C |

- |

Lindt Milk, Red |

Didn't like |

| North America |

Raleigh, USA. 14°C |

- |

Hershey's Kisses, Silver |

Confirmed, did not like. |

Observations and Experimental Conclusion:

This turned out to be much more interesting than I expected! When I salted my tongue first, I could tolerate chocolate; without it, I couldn't. That alone rules out a lot of other explanations. Something chemical is clearly happening. Salt suppresses bitter taste receptors and seems to blunt the sharp, roasted edge of chocolate's aroma, which makes bitterness the strongest candidate for what's been driving my reaction all along.

I didn't test Lindt or Hershey's with salt yet, so this isn't the final word. I'll be back in both places in early January, and I plan to run the last version of this experiment. When I do, I'll update this piece. You can follow my socials to stay posted. Until then, consider this a working conclusion, one I didn't expect to reach, but one that finally feels explanatory.

Cheers to Halloween 2009, Jim O'Shaughnessy and Jose Sabau for convincing me that they would enjoy this piece if nobody else did, Rabbitholeathon for facilitating this rabbit hole, Shan and Rob for reading drafts, to Dr. Briggs at UNC, and to me for not liking chocolate!